The Use of AI to Generate Reference Images

For those short on time: The key points are in bold

by Jim Witherell

July 13, 2024

Artificial Intelligence (AI) is the buzzword of the day, evoking plenty of emotion as it is discussed across the citizenry. To some, it threatens to be the downfall of society as we know it. To others, it is the promise of a fantastic new world, with lofty expectations similar to those of the Space Age or electricity. AI is going through the same early mania-driven cycle other technologies have gone through: Telephones and radio were going to turn people away from reading or even having conversations with one another. Televisions would turn everyone into glassy-eyed zombies. Computerphobia was a thing in the 1990s. The Internet would bring the scourge of society right into our homes. Mobile phone radio waves cause cancer. As has happened before, wild speculation about AI's impact will give way to real-world experience in the coming years. An apocalyptic prediction or two may have a thread of truth. Still, for the most part, these forecasts become examples of our naivety at the early stages of a new technology's march into society.

As people innovate with a new piece of tech, new possibilities emerge. Leigh Witherell's novel use of AI as a source for reference images for her paintings is one such innovation. Upon first blush, questions are asked: Is she using AI to generate the paintings themselves? (No.) Is she painting in an altogether new way? (No.) What exactly is new in her art's development? (Read on!) Is this a shortcut that cheapens art in some way? (No.) Let's explore it…

To begin with, throughout time, artists compose or plan what they will eventually put to canvas, which is a discussion unto itself. But first, they need images to work with. Some hit the street with a camera, capturing compelling images and perspectives to select from as part of their process. Others take their sketch pad or easel to the beach and draw what they see. A sunset. Waves crashing on the shore. A couple holding hands while walking along the coast. Sandpipers while they race to and fro along the wet sand. Yet others use only their mind's eye, composing merely from imagination and documenting the design on a sketch pad. Any given artist uses various methods to compose their artwork. Let's fast forward: now the artist has their composition in mind.

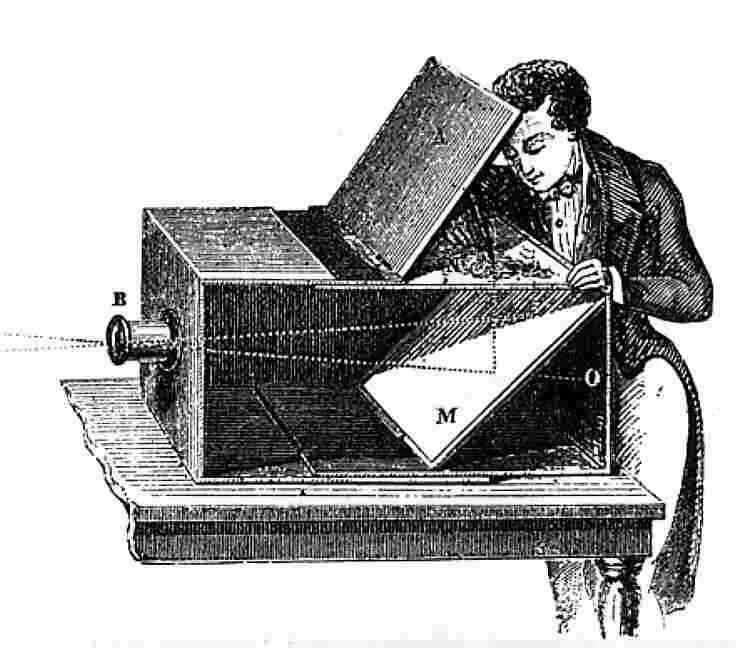

Next is the task of transferring these images to the canvas, which can happen in numerous ways. Our artist is now in the studio, implements are in hand, the environment is adjusted, and the medium of choice is before the artist and the work is ready to begin. Reference images (e.g., sketches, photographs) are carefully placed within reach and ready. Tools may be used to aid in working with the images. Da Vinci and Rembrandt were known to use a device called the camera obscura (Fig. 1). John Hockney, Gustave Caillebotte, and John W. Audubon sometimes used the slightly more refined camera lucida (Fig. 2). For many artists, it is simply "There's the image, and here's the paint, brushes, and canvas. Go."

Now to get to work. All that pre-work gives way to something that looks much more like the romantic picture the layman imagines: the noble artist is alone in the studio, toiling over the medium. The day gives way to night. A meal is skipped as they're on a roll. An unexpected late-night session occurs when an epiphany brings the artist out of bed and into the studio, grabbing the brush to capture the fresh nocturnal inspiration. Eventually, the piece is done.

We've recapped a typical sequence of events. Now, let's look at Leigh's process and notice the differences:

Today, Leigh's medium of choice is usually canvas. Regarding the image, at times, she stays true to it, and other times, she departs from certain aspects, sometimes on the same canvas. Perhaps she is OK with the subject's face, but now that's a sunset instead of a sunrise. Her source images are nearby; this time, the composition is in her mind's eye. Gradually, the artwork comes to life. Finally, after days and sometimes even weeks, the piece is done! A smile emerges as Leigh leans back in the chair. This seems unremarkably similar so far.

But here is one of two critical differences in Leigh's process in this modern era: an essential tool is her trusty iPad instead of photos or sketches, delicately located next to the canvas. She can zoom in and adjust aspects to see the detail of interest in the image she developed before the canvas was even placed on the easel. When she's ready for a different image, it takes just a few taps, and now she has what she needs in seconds. Hundreds of images in her library are with her in full resolution and can be quickly called up on demand at any moment.

The second and arguably more intriguing difference is Leigh's use of AI to create the source images themselves. In contrast, a traditional artist may jump in the car with their camera or sketch pad and go out to find pictures to capture. She iteratively prompts her AI generators to create images to be manipulated, altered, modified, tweaked, and finally frozen when she has what she wants. In many of these cases, the starting point is her photos as the initial input into AI's "meat grinder" to ingest and re-imagine. In other cases, she only gives written prompts describing what she is looking for as the starting point, and then through many iterations, the files are course-tuned and finely adjusted until it is now what she wants. The AI-generated face is analogous in every way to the random face of a pedestrian in the scene as a camera snaps. The revolutionary difference is that Leigh manipulates the image to choose the eye color, hairstyle, or outfit before her image is finalized. By contrast, the traditional artist must make those changes after taking the picture.

From there, she can create a collage of images, like in her 2023 piece "We Are the Story” (Fig. 3). In this case, she created a collection of pictures inspired by numerous interviews she conducted with parents worldwide. She arranged these to create a tapestry illustrating parents' grief when losing a child. She sparingly modified the individual subjects while more organically devising the composition. Another example is "Ghost of You," where Leigh starts with a selfie her daughter took with her cat (Fig. 4). She arrived at her final image through many iterations and fell in love with it (Fig. 5). Leigh decides the final painting (Fig. 6) will not stray very far from the digital image.

Leigh’s development of this method of acquiring source images and composing her works is attracting attention. Keep in mind, though, that she is an artist who has quite a lot to say through her artwork. Check back occasionally to see where her attention has been focused.

(Fig 1) A camera obscura box with mirror, with an upright projected image at the top. - Wikipedia

(Fig 2) Camera Lucida in use drawing small figurine. illustration from the Scientific American Supplement, January 11, 1879. - Wikipedia

(Fig 3) - "We are The Story" - An example of Leigh's composition using many source images in a collage.

(Fig 4) Source image from snapshot as AI input basis for "Ghost of You"

(Fig 5) Final version of AI generated digital image used as Leigh's source image for her acrylic canvas painting "Ghost of You"

(Fig 6) Leigh Witherell's acrylic canvas painting "Ghost of You"